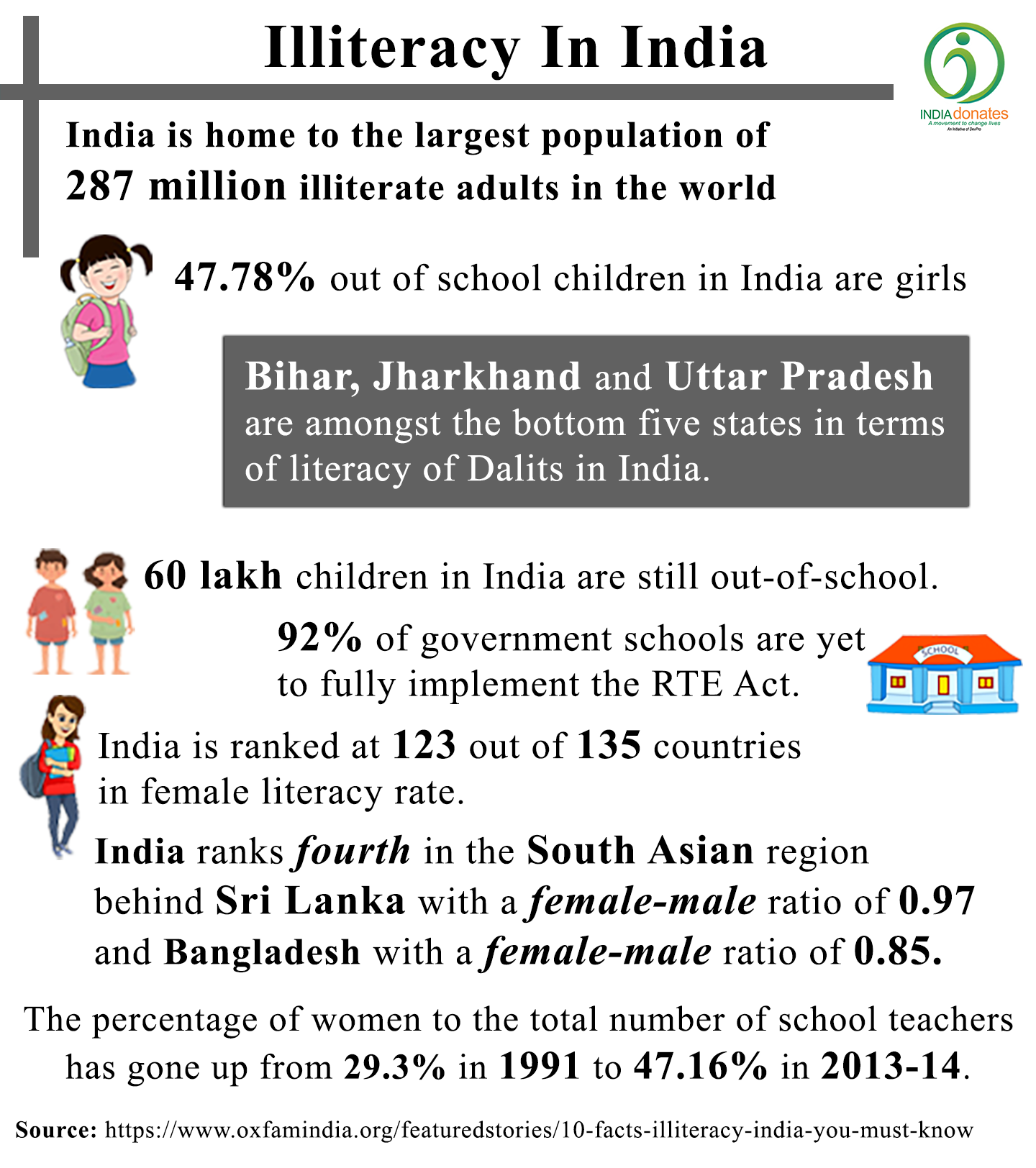

With a shrinking GDP, (24% in the first quarter), border skirmishes, and a pandemic to battle with, imparting education of a global class might take a backseat. Although we are in the midst of a digital revolution, accessibility to a holistic education is still a future cry. International Literacy Day is celebrated on Sept 8th, and undoubtedly there has been some positive trajectory. India’s literacy rate increased six times since Independence, however, the individual figures show how sluggish our education growth has been.

These numbers give us a vivid picture of the apathetic situation of education in India. The problems associated with education are multi-layered embodying some of the critical social issues like caste and gender discrimination, urban-rural divide, economic disparity, teacher student ratio, etc. While the government is needed to uphold the policies and look after the implementation, there is much-needed work at the local level to de-stigmatize education from societal shackles. NGOs play a huge role in demystifying education for education sakes.

During my stint working at the grass-root level on education, I had first-hand experienced many problems that are still prevalent in the far-flung areas of India, and I would roughly divide it into three broad categories.

Gendered Education- From the above table you can get a picture of how education is gendered. It empowers one while the other is still marginalised and oblivious. Although at the urban level we have repeatedly seen girls outperforming boys in ICSE and CBSE boards, one might be trapped into believing otherwise. However, gender discrimination is still widely prevalent. As policymakers come up with varied schemes to allure girls to school, it is important to consider the moot area of intervention should not just be getting more enrolments but how schools can be made a haven for all kids

Lack of Infrastructure – The raging pandemic, has exposed multiple fractures in our economy, primarily the health infrastructure; but it also jeopardised our education system, which was showing some recovery. In urban areas, the private players were quick to jump to a readily available digital infrastructure. On the other hand, rural India is still struggling to create a synergy of the archaic system of imparting education with adapting the new channels. A recent reportage by BBC showed how villages are taking a more primitive approach to impart education during such tough times. Teachers are using the Barter system to teach students in return for vegetable goods. At a micro-level these might be viewed as a temporary regression, juxtaposed to the pandemic, however, it also exposes the volatile nature of our education system. Indians in their lexicon laud these make-do activities as ‘Jugaad’ and while we might pat our backs, it is important to remember that Education cannot be a Jugaad. There are multiple examples online, that reflect the spirit of make-do; these stories are inspiring, but as a society, it also reflects our broken structures and systems.

Building a digital infrastructure is a new phenomenon, and maybe in due course, our digital interventions will reach far and wide. But many parts of India, still do not have a functional brick and mortar. India spends 4.6 percent of its total GDP on education, and ranks 62nd in total public expenditure on education per student, according to an IMD report. In comparison to OCED countries, India’s spending on public education is extremely low. One of the reasons, we still lack toilets, playgrounds, adequate access to schools. These infrastructural inadequacies are preying on widening the education gap in rural and urban areas and exposing the inequities. With the incoming National Education Policy (NEP), the government is expected to increase the expenditure on public education, but to what scale can it be achievable now that the priorities have again shifted due to COVID – 19, is yet to be seen.

Mind-set Shift – One of the key areas of intervention and largely overlooked is the mind-set shift within families. Children in India, are considered a big force of labour, be it a girl or a boy. From an early age, children are taught to learn specific skills that can generate income for the family. In the last 10 years, we have seen national campaigns and even private campaigns that propagate education as a stepping stone for all children.

However, when it comes to practicing the same, numerous villages still fail to adhere to it owing to their socio-economic background. While India has been able to incentivise joining schools, it has repeatedly failed to make this mind-set shift unconditionally, as it comes in direct conflict with income generation.

As NGOs, if we intend to make a scalable change, it cannot just be about imparting education. The question should be what is literacy, what kind of education do we intend to impart and whom should we target. A largely overlooked target of education is both parents and teachers. While they are the decision-makers in their nucleus, they are not thoroughly engaged both by the government and the NGOs. It is important to take into cognizance the fact that rural India shares a close-knit bond, and much of their systems work in community participation. Parents and teachers who play a decisive role in a child’s future should be first capacitated and engaged meaningfully right from understanding the curriculum and what benefits education could reap for the child, family, and society. Creating community-based leadership can also motivate the guardians to propagate and preach.

Within these three categories, there are multiple other problems, that we need to address head on, like the definition of Literacy. According to Census 2011, “A person aged seven and above who can both read and write with understanding in any language, is treated as literate. A person, who can only read but cannot write, is not literate.” This definition narrows our understanding of holistic education. Another big concern is the RTE Act, which led to increased enrolment in schools, but it only considered children in the age group of 6-14. However, with the new National Education Policy, this age group bracket is intended to increase, encompassing children from 3-18 years. This is a welcome move, and we are likely to see more enrolments in the coming years. The NEP modelled after Dr. K Kasturirangan’s committee report also has emphasized on vocational training and avoiding rote memory. In my understanding, while vocational training is a must and has already evolved, thanks to just interventions from NGOs, our understanding of learning, memorising, processing and examining, needs hand-holding support. Instead of establishing syllabi, NGOs and governments should focus on learning new education methodologies from around the world, that focus on quality rather than quantity.

In due course, we will emerge from the pandemic, with hopefully better scientific acumen, digital viability, understanding of anthropology. But meanwhile, we cannot let down our guards on issues pertaining to education, health, environment, economy. On this International Day of Literacy, - teachers, thinkers, leaders, parents, and most importantly youth should think about the future of education, and how we can reinvigorate our education system in our individual capacity, by looking beyond the legalities and natural rights to education.